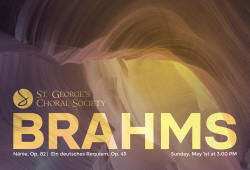

St. George’s Choral Society presents its annual spring concert featuring two

pieces by Brahms: Nänie, op. 82, and Ein deutsches Requiem,

op. 45, or A German Requiem, widely considered a choral music

masterpiece and Brahms’s longest and most grandiose single work. A shorter, more

concise piece, Nänie might be thought of as a secular companion to the

biblically-oriented Requiem. Both works focus on the theme of grieving and

solace for the bereaved.

St. George’s Choral Society presents its annual spring concert featuring two

pieces by Brahms: Nänie, op. 82, and Ein deutsches Requiem,

op. 45, or A German Requiem, widely considered a choral music

masterpiece and Brahms’s longest and most grandiose single work. A shorter, more

concise piece, Nänie might be thought of as a secular companion to the

biblically-oriented Requiem. Both works focus on the theme of grieving and

solace for the bereaved.

Nänie

That death can be a catalyst for great art is a dictum that Brahms knew intimately better than most people. His motivation for Nänie – the word is the germanized version of the Latin “nenia,” which means funeral ode – derived from a concrete source: the untimely passing of his close friend Anselm Feuerbach, the German classical painter.

The text is lifted from Friedrich Schiller, the poet and playwright who is second only to Goethe in the German literary canon, and features references to three Greco-Roman myths: Orpheus and Eurydice; Aphrodite (Venus) and Adonis; and the death of Achilles, all of which deal with mortality and place in the foreground the importance of properly mourning the passing of our loved ones. Given that stories from Greek mythology often formed the basis for Feuerbach’s paintings, Brahms’s aesthetic decision here could not be more appropriate.

While an elegy may be more morose in tone, an ode is celebratory by definition. Not surprisingly, Nänie – it was composed in 1881, so it is one of his later works – brims with an understated buoyancy. It kicks off with an unforgettable line from Schiller, “Even the beautiful must die,” which in many serves as the crux for the entire piece, and is brilliantly drawn out by Brahms. Nänie will be sung by the chambers singers.

A German Requiem

In many ways, Brahms was an inscrutable being who guarded his private life like the Crown Jewels. Where the man may have tended toward reticence and recalcitrance, his music, on the other hand, is accommodating, generous and, above all, inviting. This is certainly the case with the German Requiem. As commentators have noted over the years, the qualifier “German” can easily be substituted with “Human” or “Mankind.” E.M. Forster’s famous injunction, “Only Connect,” comes to mind as a fitting descriptor for Brahms’s unerring catholicity.

It is worth noting that Brahms’s chef d’oeuvre was produced in a tempest of great internal conflict. According to the literary critic Harold Bloom, the history of literature can be seen as a continuous series of generational conflicts wherein the contemporary writer wrestles with the “anxiety of influence” from his forebears. The “agon” produced can destroy the weak-willed writer; for the strong one, it leads to aesthetic revelation.

In the case of Brahms, the composer was wracked by the long, inky shadow cast by Beethoven. His mentor Robert Schumann surely did not assuage his agitations when he publicly compared his student to the greatest figure in Western classical music history, a notion that many people at the time no doubt would have scoffed at. History has proven Brahms right, though. He has carved out his own space in the canon. His place is secure, and one only need to turn to the German Requiem to know that this is evident.

As with Nänie, the Requiem (composed between 1865 and 1868) was inspired by the death of a real personage in Brahms’s life. This person is thought to be Brahms’s mother, but there is also the possibility that Schumann, a psychotically-embattled man who passed away in 1856 in an insane asylum, also served as as distant source.

Unlike the convention in his time, Brahms did not derive the work’s text from the Latin bible. Instead he patched it together from the Lutheran bible and the Apocrypha, unsanctioned, heterodox biblical books not included in the official Hebrew version. Composed of seven movements, the Requiem seemingly embodies all the complicated facets of the human condition. Somber and dirge-like in the beginning, the work ends on a rousing note that suggest the parting of darks clouds and the first stabs of glorious sunlight. And who can forget the apocalyptic sixth movement, fervid and uptempo, featuring the memorable lines from 1 Corinthians 15:55, “Death, where is your sting? Hell, where is your victory?”

SGCS’s four-hand piano arrangement of the German Requiem will be sung by the full ensemble. The concert will feature two outstanding vocal soloists, Rebecca Farley and Edmund Milly. You can read more about them here. James Bassi and Eric Sedgwick will be at the piano.

The concert will take place May 1 at 3 PM at St. George’s Church, 7 Rutherford Place, and will also be streamed online. Tickets are $30, available online and at the door. More information is here.

Sean Nam is on the board of the St. George's Choral Society.